lecture on 29 July

1.What is our life?’, by Sir Walter Raleigh

What is our life? A play of passion,

Our mirth the music of division;

Our mothers’ wombs the tiring houses be,

Where we are dressed for this short comedy;

Heaven the judicious sharp spectator is

That sits and marks still who doth act amiss;

Our graves that hide us from the searching sun

Are like drawn curtains when the play is done.

Thus march we playing to our latest rest —

Only we die in earnest, that’s no jest.

2.Sonnet 54

by Edmund Spenser

| Of this world's theatre in which we stay, My love, like the spectator, idly sits; Beholding me, that all the pageants play, Disguising diversely my troubled wits. Sometimes I joy when glad occasion fits, And mask in mirth like to a comedy: Soon after, when my joy to sorrow flits, I wail, and make my woes a tragedy. Yet she, beholding me with constant eye, Delights not in my mirth, nor rues my smart: But, when I laugh, she mocks; and, when I cry, She laughs, and hardens evermore her heart. What then can move her? if nor mirth nor moan, She is no woman, but a senseless stone. 4.TOTTEL’S MISCELLANY Songes and sonettes, written by the ryght honorable Lorde Henry Haward late Earle of Surrey, and others. Songes and sonettes, written by the ryght honorable Lorde Henry Haward late Earle of Surrey, and others.

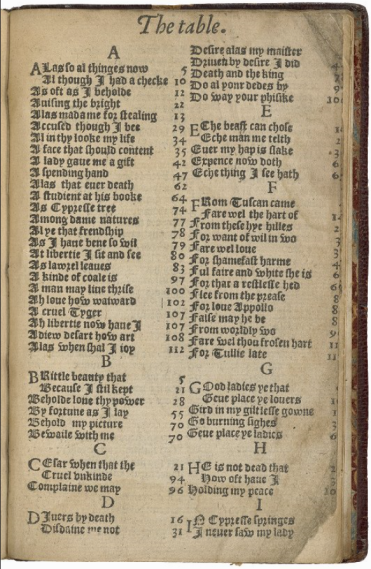

5th June 1557 edition English Short Title Catalogue record 1st 1559 edition English Short Title Catalogue record 1565 edition English Short Title Catalogue record 1574 edition English Short Title Catalogue record Songes and Sonettes was by far the most experimental book Tottel printed and also the most popular with his contemporaries. It was one of the first, if not the first anthology of English poetry. It included secular verse by the English nobleman Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (b. 1516/1517 – 1547), the courtier Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503 – 1542), Nicholas Grimald (b. 1519/20, d. in or before 1562), the humanist scholar, poet and dramatist and several anonymous ‘uncertain’ authors . Two editions appeared in 1557. The first edition was published on the 5th of June and included 271 poems, with 40 attributed to Surrey, 97 to Wyatt, 40 to Grimald, and 94 to ‘Uncertain Authors’. The second edition was printed very shortly afterwards on the 31st of July. This edition was substantially revised and reorganised, the poems attributed to Surrey remained unchanged, one of the Wyatt’s poems was removed, the number of poems attributed to Grimald decreased significantly to 10, and those attributed to ‘Uncertain Authors’ increased to 134. The poems cover a variety of subjects such as friendship, war, politics, death and love. The full text of an early twentieth century edition edited by Edward Arber who was the first to refer to it as Tottel’s Miscellany is available online. Tottel appears to have a been a very cautious businessman at every stage of his career, so it is interesting that he was willing to take the financial risks involved with printing the first edition of Songes and Sonettes. There was no established market for printing anthologies of verse in English, although some French and Italian printers during the first half of the sixteenth century had successfully published miscellanies of secular vernacular poetry. The preface Tottel wrote to the first edition refers to this and suggests that the works of ‘good Englishe writers’ should also be celebrated. In the introduction to the 2011 Penguin Books edition of Tottel’s Miscellany, the editors refer to this preface to the miscellany, The Printer to the Reader. In it Tottel implies that he is providing the general public with access to works that had been hoarded by the aristocracy. A comparison is made with the printing of common law texts which also involved bringing the public in on something that had previously been kept from them. Clearly, in addition to his business concerns, Tottel was conscious of the humanist role of a printer to bring written works previously reserved for an elite few to a much wider audience. The exact extent of Tottel’s involvement in organising the text of the miscellany is not known and there is a long-standing question of who, if anyone, edited the poems. The two main manuscripts that the poems appear to come from, the Egerton MS. 2711 and the Arundel Harington, indicate that the versions in the miscellany were substantially revised before publication. Nicholas Grimald has often been considered a likely editor because of his association with Tottel at this exact period and his widespread literary activities. The other two noteworthy theories are that a group of young lawyers from the Inns of Court connected to Tottel could have edited the works, or that it was Tottel himself. The main evidence supporting the theory of Tottel as editor is that he printed other volumes of verse, was connected contemporary poets like Grimald and that the alterations made to his edition of John Lydgate’s Fall of Princes from Richard Pynson’s 1527 edition are of a similar style to those made to the poems in the miscellany from their manuscript versions.  The recent 2011 Penguin edition of Tottel’s Miscellany has a detail from The burning of the remains of Martin Bucer and Paul Fagius on Market Hill in Cambridge in 1557 from Acts and Monuments by John Foxe. Songes and Sonettes was published during the reign of Mary, when the burning of Protestant ‘heretics’ was at its peak in the summer of 1557. Tottel’s political caution is evident in the selection of the poems. There are none that attack the Marian regime but there are also none that directly praise it. One particular poem, 168. A praise of his Ladye included praise of Mary in a manuscript version and this is edited out of the printed version. Also, one of Wyatt’s most famous poems Whoso list to hunt which is often thought to be about Anne Boleyn, the mother of the future Elizabeth I, also appears to have been deliberately excluded. Tottel’s Miscellany remained popular for the remainder of the sixteenth century and it is likely to have been the first contemporary English poetry that poets such as William Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser and John Donne read. In Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), Abraham Slender wishes he had his copy with him: ‘I had rather than forty shillings I had my Book of Songs and Sonnets here’. He also longs for a Book of Riddles. The fact that it was viewed as a suitable resource for a fool like Slender is a clear indication that the miscellany was no longer in vogue by the end of the century. 5.Anatomy of Melancholy, The Anatomy of Melancholy, The, in full The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is; with all the Kindes, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes and Several Cures of it: In Three Maine Partitions With Their Several Sections, Members, and Subsections, Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically Opened and Cut up, by Democritus Junior, exposition by Robert Burton, published in 1621 and expanded and altered in five subsequent editions (1624, 1628, 1632, 1638, 1651/52). The huge and encyclopaedic Anatomy of Melancholy was produced by the English clergyman Robert Burton (1577–1640). It explores a dizzying assortment of mental afflictions, including what might now be called depression. Burton considers melancholy to be an ‘inbred malady’ in all of us and admits that he is ‘not a little offended’ by it himself (p. 5). What’s in The Anatomy of Melancholy?This is the third edition (1628) of Burton’s increasingly comprehensive text, first published in 1621 and expanded from 1624 to 1651. The work is divided into three sections. The first considers the nature, symptoms and diverse causes of melancholy. These causes range from God to witches and devils, poverty and imprisonment, parents and ‘overmuch study’, ‘desire of revenge’, or ‘overmuch use of hot wines’. The second section discusses cures such as exercise and diet, purging, blood-letting and potions. The third focuses on two particular types – love melancholy and religious melancholy. Burton’s work is richly varied and at times bewilderingly rambling. It shifts from sad to self-reflexive, from satirical to serious, including an eclectic mix of quotations (many in Latin) from literature, philosophy and science. The engraved title pageThis edition includes, for the first time, an elaborate title page engraved by Christian Le Blon, with portraits of Democritus (the laughing philosopher) and the author (in the persona of Democritus Junior). These are placed alongside symbols of melancholic types including a ‘madman’ who reminds us, ominously, that ‘twixt him and thee, ther’s no difference’. Male and female melancholy: Hamlet and OpheliaMany agree with Claudius’s claim that ‘there’s something in [Hamlet’s] soul’ which seems to be ruled by ‘melancholy’ (3.1.164–65). It was a common, even fashionable malady in Elizabethan England, associated with sadness and abnormal psychology, but also refinement and male intellect. Yet, as Elaine Showalter has noted, female melancholy was considered to fall into a whole different category, connected not with genius but with sexuality and sexual frustration. Burton gives us an insight into how this might have been viewed in the early modern era. In the section on ‘Maides, Nunnes, and Widows’, he claims that ‘noble virgins’ are particularly affected by ‘vitious vapours which come from menstruous blood’ (p. 193). He reports shocking tales of nuns who rebel against their ‘enforced temperance’ and express their sexuality, leading to ‘frequent’ abortions and ‘murdering infants in their Nunneries’ (p. 196). For him, the ‘surest remedy’ is to see them ‘married to good husbands’ where they can fulfil their ‘desires’, and put out the ‘fire of lust’ (pp. 194–95). Hamlet expresses the idea that ‘Frailty’ is particularly female (1.2.146). Ophelia, in Acts 4 and 5, is seen by her brother Laertes as a ‘document in madness’ (4.5.178). As in Burton’s Anatomy, her insanity is connected with both virginal innocence and explicit sexuality. Yet, contrary to Burton, Hamlet bitterly suggests that she should go to a nunnery (3.1.120). Love melancholy: Benedick and BeatriceBurton reveals a knowledge of Shakespeare, using the playwright’s characters as definitive examples of particular psychological types (as Sigmund Freud would do centuries later). For Burton, lovers who at first ‘cannot fancie or affect each other, but are harsh and ready to disagree’ are ‘like Benedict and Betteris in the comedy’, Much Ado About Nothing. He claims that the best solution is to push the couple into marriage, so that love will grow out of closeness: ‘by this living together in a house, conference, kissing, colling [or embracing], and such like allurements, [they will] begin at last to dote insensibly one upon another’ (p. 443). Burton seems to sidestep the idea that, in Shakespeare’s play, the couple might love each other even before their friends intervene; we might see their witty disagreements as a subtle sign that they already 'fancie' each other. Robert Burton’s tomb in Christ Church, Oxford, bears an enigmatic Latin inscription suggesting that ‘Melancholy gave life and death’ to its occupant. Historians and antiquaries have often speculated about its precise meaning. A persistent rumour perpetuated by Burton’s contemporary, the biographer and Oxford gossip Antony Wood, implied that its origins lay in Burton’s reading of an astrological chart predicting his own death in 1640. The melancholic Burton, the gossips suggested, committed suicide and thereby grimly verified the astrologer’s prediction. The evidence on either side is scant, but the rumour has persisted. Thus melancholy, a complex and peculiarly pre-modern disease, may well have killed Burton: it certainly must have occupied much of his time while he lived. Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, which was first published in 1621 and reissued in several subsequent editions in the 17th century, was a vast, erudite behemoth of a book. The Anatomy expanded relentlessly in Burton’s lifetime, since he constantly reworked the text and added extra material to each new edition. It won a wide readership among his learned contemporaries across Europe and remained popular long after Burton’s death. It seems that many of his later readers viewed the Anatomy as both a useful storehouse of impressive learning that could be recycled for their own purposes and, occasionally, as a source of practical advice. One 17th-century physician, Richard Napier, reportedly used some of the remedies he found in Burton’s work to treat his patients. What exactly did the Anatomy anatomize? Any reasonable answer to this question involves stepping back into an unfamiliar and complicated mental world. In the 16th and 17th centuries, melancholy was typically defined in the medical literature (which itself drew on Aristotelian, Hippocratic, Galenic and other classical sources) as a form of delirium (or mental distress) characterized by the impairment of the patient’s mental faculties (typically reason or imagination), combined with a tell-tale absence of fever and accompanied by the passions of fear and sorrow. The early modern understanding of melancholy drew on humoural theory to explain its basis and effects—specifically, it connected melancholy to an excess of one humour, in particular black bile. Medical discussions of the humours were complex, but were built on the assumption that a healthy body exhibited equilibrium between the four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile). Each humour had its own distinct characteristics derived from the elements of heat, coldness, wetness and dryness. Blood was hot and moist, yellow bile hot and dry, phlegm cold and moist and black bile cold and dry. Any disruption to this equilibrium was potentially harmful, and produced disorder and disease. The basic humoural building blocks were multiplied by classical and later authors to produce a nuanced analysis of the many possible temperaments or mixtures of humours. The underlying assumption of this account was that the ‘perfect’ humoural mixture rarely occurred—most people were therefore unbalanced in respect to their humours. In the case of melancholy, an excess of the cold and dry humour of black bile produced symptoms affecting both body and soul together—making melancholy what we might anachronistically call a somatic and psychic disorder. Consequently, Burton’s Anatomy contained much discussion of the structure and functions of the body, mostly towards the start of the first part of the work, where he noted that he ‘held it not impertinent to make a brief digression of the anatomy of the body and faculties of the soul, for better understanding of that which is to follow’. Burton cannibalized the work of well-known 16th-century anatomists and medics such as Andreas Vesalius and Jean Fernel for this part of the book. But his approach to melancholy was based on more than simply medical knowledge: among the ‘divers writers’ he cited were works of classical literature, theology and history. This omnivorous attitude to his sources was driven partly by the therapeutic aims of the Anatomy. Burton clearly saw his project as an enterprise driven by the hope of alleviating or curing melancholy, although a dark thread of pessimism about the chances of achieving this goal runs through the book. The Anatomy was also an extended exercise in self-therapy. ‘I write,’ Burton noted in its opening pages, ‘of melancholy, by being busy to avoid melancholy’. A cure might be found in the pastoral care of a priest, or in work (Burton commanded the reader to ‘Be not solitary, be not idle’) as much as in the apothecary’s shop or the physician’s consulting rooms. As a disorder, melancholy therefore inhabited a strange space between the expertise of medics, pastors and moral philosophers. |

Comments

Post a Comment